MOSS LANDING, CA — Killer sponges sound like creatures from a B-grade horror movie. In fact, they thrive in the lightless depths of the deep sea. Scientists first discovered that some sponges are carnivorous about 20 years ago. Since then only seven carnivorous species have been found in all of the northeastern Pacific. A new paper authored by MBARI marine biologist Lonny Lundsten and two Canadian researchers describes four new species of carnivorous sponges living on the deep seafloor, from the Pacific Northwest to Baja California.

A far cry from your basic kitchen sponge, these animals look more like bare twigs or small shrubs covered with tiny hairs. But the hairs consist of tightly packed bundles of microscopic hooks that trap small animals such as shrimp-like amphipods. Once an animal becomes trapped, it takes only a few hours for sponge cells to begin engulfing and digesting it. After several days, all that is left is an empty shell.

MBARI researchers videotaped the new sponges on the seafloor, then collected a few samples for taxonomic work and species-reference collections. Back in the lab, when they looked closely at the collected sponges, the scientists discovered, as Lundsten put it, "numerous crustacean prey in various states of decomposition."

Sponges are generally filter feeders, living off of bacteria and single-celled organisms sieved from the surrounding water. They contain specialized cells called choancytes, whose whip-like tails move continuously to create a flow of water which brings food to the sponge. However, most carnivorous sponges have no choancytes. As Lundsten explained, "To keep beating the whip-like tails of the choancytes takes a lot of energy. And food is hard to come by in the deep sea. So these sponges trap larger, more nutrient-dense organisms, like crustaceans, using beautiful and intricate microscopic hooks."

The spikiness of two these new sponges is reflected in the name of their genus—Asbestopluma. One of these, Asbestopluma monticola was first collected from the top of Davidson Seamount, an extinct underwater volcano off the Central California coast (monticola means "mountain-dweller" in Latin).

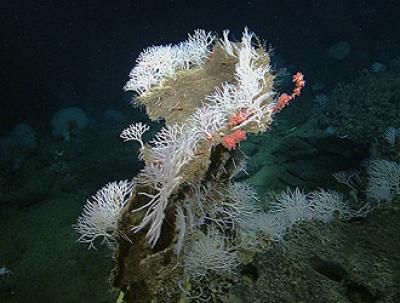

A large group of Asbestopluma monticola sponges grow on top of a dead sponge on Davidson Seamount, off the Central California coast.

(Photo Credit: © 2006 MBARI)

A second new species, Asbestopluma rickettsi, was named after marine biologist Ed Ricketts, who was immortalized in John Steinbeck's book, Cannery Row. This sponge was observed at two locations offshore of Southern California. At one of these spots, the sponge was living near colonies of clams and tubeworms that use bacteria to obtain nutrition from methane (natural gas) seeping out of the seafloor. Although A. rickettsi has spines, the researchers did not see any animals trapped on the specimens they collected. Ongoing research suggests that this sponge, like its "chemosynthetic" neighbors, can use methane-loving bacteria as a food source.

The third and fourth new species of carnivorous sponges were also observed near communities of chemosynthetic animals. However these communities were associated with deep-sea hydrothermal vents, where plumes of hot, mineral-rich water flow out of the seafloor.

One new species, Cladorhiza caillieti, was found on recent lava flows along the Juan de Fuca Ridge, a volcanic ridge offshore of Vancouver Island. The fourth sponge, Cladorhiza evae, was discovered far to the south, in a newly discovered hydrothermal vent field on the Alarcon Rise, off the tip of Baja California. Specimens of both these sponges had numerous prey trapped among their spines.

Although it's clear that the sponges with trapped animals were consuming their crustacean prey, the authors are looking forward to the day when they will actually get to see this process in action. Until then, horror-movie fans will have plenty to look forward to—as Lundsten and his coauthors noted in their recent paper, "Numerous additional carnivorous sponges from the Northeast Pacific (which have been seen and collected by the authors) await description, and many more, likely, await discovery."