Induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) taken from a patient hold great therapeutic potential for many diseases. However, studies in rodents have suggested that the body may mount an immune response and destroy cells derived from iPSCs. New research in monkeys refutes these findings, suggesting that in primates like us, such cells will not be rejected by the immune system. In the paper, publishing September 26 in the ISSCR's journal Stem Cell Reports, published by Cell Press, iPSCs from nonhuman primates successfully developed into the neurons depleted by Parkinson's disease while eliciting only a minimal immune response. The cells therefore could hold promise for successful transplantation in humans.

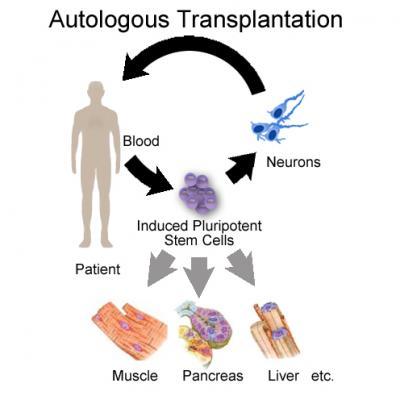

iPSCs are cells that have been genetically reprogrammed to an embryonic stem-cell-like state, meaning that they can differentiate into virtually any of the body's different cell types. iPSCs directed to differentiate into specific cell types offer the possibility of a renewable source of replacement cells and tissues to treat ailments, including Parkinson's disease, spinal cord injury, heart disease, diabetes, and arthritis.

Studies in rodents have suggested that iPSC-derived cells used for transplantation may be rejected by the body's immune system. To test this in an animal that is more closely related to humans, investigators in Japan directed iPSCs taken from a monkey to develop into certain neurons that are depleted in Parkinson's disease patients. When they were injected into the same monkey's brain (called an autologous transplantation), the neurons elicited only a minimal immune response. In contrast, injections of the cells into immunologically unmatched recipients (called an allogeneic transplantation) caused the body to mount a stronger immune response.

This illustration shows the image of autotransplantation. The paper shows evidence only for neural cells and the brain, not for other organs. Immunogenicity in other organs needs to be explored.

(Photo Credit: Stem Cell Reports, Morizane et al)

"These findings give a rationale to start autologous transplantation—at least of neural cells—in clinical situations," says senior author Dr. Jun Takahashi, of the Kyoto University's Center for iPS Cell Research and Application. The team's work also suggests that transplantation of such neurons into immunologically matched recipients may be possible with minimal use of immunosuppressive drugs.

Source: Cell Press