Researchers from North Carolina State University have developed a new technique for creating stronger, lightweight magnesium alloys that have potential structural applications in the automobile and aerospace industries.

Engineers constantly seek strong, lightweight materials for use in cars and planes to improve fuel efficiency. Their goal is to develop structural materials with a high "specific strength," which is defined as a material's strength divided by its density. In other words, specific strength measures how much load it can carry per unit of weight.

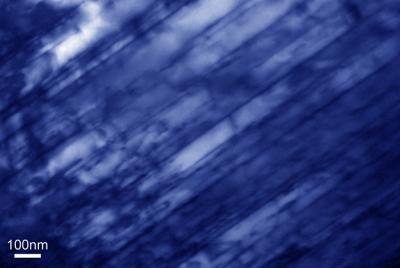

Researchers at NC State focused on magnesium alloys because magnesium is very light; on its own, though, it isn't very strong. In the study, however, the researchers were able to strengthen the material by introducing "nano-spaced stacking faults." These are essentially a series of parallel fault-lines in the crystalline structure of the alloy that isolate any defects in that structure. This increases the overall strength of the material by approximately 200 percent.

Nano-spaced stacking faults are parallel fault-lines in the structure of the magnesium alloy that increase the strength of the material by 200 percent.

(Photo Credit: Yuntian Zhu, North Carolina State University)

"This material is not as strong as steel, but it is so much lighter that its specific strength is actually much higher," says Dr. Suveen Mathaudhu, a co-author of a paper on the research and an adjunct assistant professor of materials science and engineering at NC State under the U.S. Army Research Office's Staff Research Program. "In theory, you could use twice as much of the magnesium alloy and still be half the weight of steel. This has real potential for replacing steel or other materials in some applications, particularly in the transportation industry – such as the framework or panels of vehicles."

The researchers were able to introduce the nano-spaced stacking faults to the alloy using conventional "hot rolling" technology that is widely used by industry. "We selected an alloy of magnesium, gadolinium, yttrium, silver and zirconium because we thought we could introduce the faults to that specific alloy using hot rolling," says Dr. Yuntian Zhu, a professor of materials science and engineering at NC State and co-author of the paper. "And we were proven right."

"Because we used existing technology, industry could adopt this technique quickly and without investing in new infrastructure," Mathaudhu says.

Source: North Carolina State University