Researchers from Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine and the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute have made a fundamental discovery relevant to the understanding and treatment of heart failure – a leading cause of death worldwide. The team discovered a new molecular pathway responsible for causing heart failure and showed that a first-in-class prototype drug, JQ1, blocks this pathway to protect the heart from damage.

In contrast to standard therapies for heart failure, JQ1 works directly within the cell's command center, or nucleus, to prevent damaging stress responses. This groundbreaking research lays the foundation for an entirely new way of treating a diseased heart. The study is published in the August 1 issue of Cell.

"As a practicing cardiologist, it is clear that current heart failure drugs fall alarmingly short for countless patients. Our discovery heralds a brand new class of drugs which work within the cell nucleus and offers promise to millions suffering from this common and lethal disease," said Saptarsi Haldar, MD, senior author on the paper, assistant professor of medicine at Case Western Reserve and cardiologist at University Hospitals Case Medical Center.

Heart failure occurs when the organ's pumping capacity cannot meet the body's needs. Existing drugs, most of which block hormones such as adrenaline at the cell's outer surface, have improved patient survival. Unfortunately, several clinical studies have demonstrated that heart failure patients taking these hormone-blocking drugs still succumb to high rates of hospitalization and death. Leveraging a new approach, the research team turned their attention from the cell's periphery to the nucleus – the very place that unleashes sweeping damage-control responses which, if left unchecked, ultimately destroy the heart.

The team found that a new family of genes, called BET bromodomains, cause heart failure because they drive hyperactive stress responses in the nucleus. Prior research linking BET bromodomains to cancer prompted the laboratory of James Bradner, MD, the paper's senior author and a researcher at the Dana-Farber, to develop a direct-acting BET inhibitor, called JQ1. In models of cancer, JQ1 functions to turn off key cancer-causing genes occasionally prompting cancer cells to "forget" they are cancer. In models of heart failure, JQ1 silences genetic actions causing enlargement of and damage to the heart – even in the face of overwhelming stress.

"While it's been known for many years that the nucleus goes awry in heart failure, potential therapeutic targets residing in this part of the cell are often dubbed as 'undruggable' given their lack of pharmacological accessibility," said Jonathan Brown, MD, cardiologist at Brigham and Women's Hospital and co-first author on the paper. "Our work with JQ1 in pre-clinical models shows that this can be achieved successfully and safely."

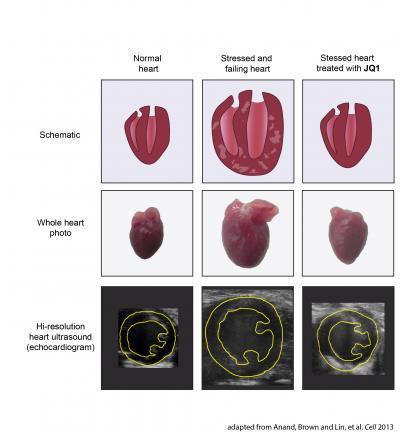

In the top row are schematic illustrations of a heart. The left and right ventricles are shown in cross section. In the middle row are photographs of whole mouse hearts as shown in Figure 3 of the Cell paper. In the bottom row are still images from high-resolution heart ultrasounds from mice taken from Figure 3 of the paper. A cross section of the left ventricle is outlined in yellow.A normal heart is shown in the left column. After stress or injury (such as mechanical overload or bombardment with adrenaline), the heart becomes enlarged, develops thickened walls that are laden with scar tissue, and eventually fails to pump blood normally (middle column). However, if the stressed heart is treated with the BET bromodomain inhibitor JQ1 (right column), this disease process is arrested. JQ1 treated hearts do not develop massive enlargement, scar tissue, or compromised pumping function. In fact, mice treated with JQ1 had maintained healthy-appearing and vigorously contracting hearts despite continuous exposure to very high levels of stress.These findings form the rationale for developing BET bromodomain inhibitors, such as the prototype drug JQ1, into novel targeted therapies for heart disease.

Reference: Anand, Brown and Lin, et al. Cell 2013.

(Photo Credit: Adapted from Anand, Brown and Lin, et al. Cell 2013.)

The team led by principal investigators Haldar and Bradner studied mice who develop classic features of human heart failure, including massively enlarged hearts that are full of scar tissue and have poor pumping function.

For one month, the team administered a single daily dose of JQ1 to the sick mice. The treated mice were protected from precipitous declines in heart function in a matter of days. Animals who received the compound saw a 60 percent improvement, as compared to an untreated control group.

"Remarkably, at the end of the experiment, the hearts of many JQ1 treated mice appeared healthy and vigorous, despite being exposed to persistent and severe stress," said Priti Anand, a researcher in Haldar's lab and co-first author on the paper. "We knew we were on to something big the first time we saw this striking response."

This collaboration started when Haldar read Bradner's landmark 2010 Nature paper describing the creation of JQ1 and its ability to transform cancer cells into healthy ones. Following an open-source approach to drug development, Bradner elected to make JQ1's chemical recipe publicly available to accelerate the creation of new treatments for patients. This synergistic approach to discovery opened the door for Haldar to work with Bradner to probe the role of BET bromodomains in the heart.

"So much has been learned from this molecule," noted Bradner. "The fundamental similarity between the biology of cancer cell growth and heart enlargement following extraordinary stress connects these mature fields of study in new and exciting ways, of immediate relevance to drug development. This study best exemplifies the power of open-source approaches to drug discovery."

In the coming months, the team will test JQ1 in preclinical models of heart failure and other cardiovascular conditions. With the jumpstart offered by Bradner's creation of JQ1, the research team hopes to one day move to clinical trials.

Source: Case Western Reserve University