Mini-kidney organoids have now been grown in a laboratory by using genome editing to re-create human kidney disease in petri dishes.

The achievement, believed to be the first of its kind, resulted from combining stem cell biology with leading-edge gene-editing techniques.

The journal Nature Communications reports the findings today, Oct. 23. The work paves the way for personalized drug discovery for kidney disease.

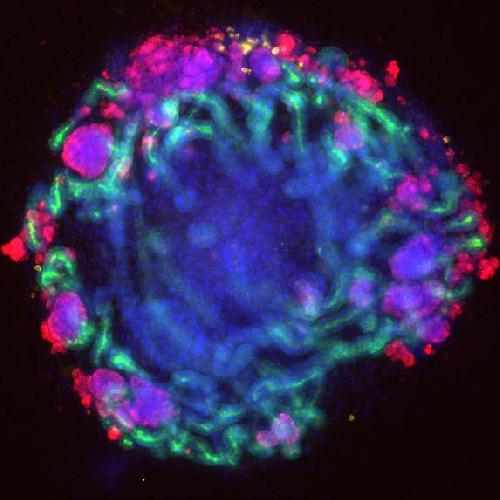

This is a mini-kidney (1 mm diameter) grown from a patient's stem cells. Credit: Benjamin Freedman & Joseph Bonventre labs

This is a mini-kidney (1 mm diameter) grown from a patient's stem cells. Credit: Benjamin Freedman & Joseph Bonventre labs

The mini-kidney organoids were grown from pluripotent stem cells. These are human cells that have turned back the clock to a time when they could develop into any type of organ in the body. When treated with a chemical cocktail, these stem cells matured into structures that resemble miniature kidneys.

These organoids contain tubules, filtering cells and blood vessel cells. They transport chemicals and respond to toxic injury in ways that are similar to kidney tubules in people.

"A major unanswered question was whether we could re-create human kidney disease in a lab petri dish using this technology," said Benjamin Freedman, who led the studies at Brigham and Women's Hospital in Boston. He is now an assistant professor of medicine in the Division of Nephrology at the University of Washington and a UW Medicine researcher.

"Answering this question," he said, "was important for understanding the potential of mini-kidneys for clinical kidney regeneration and drug discovery."

To re-create human disease, Freedman and his colleagues used the gene-editing technique called CRISPR. They engineered mini-kidneys with genetic changes linked to two common kidney diseases, polycystic kidney disease and glomerulonephritis.

The organoids developed characteristics of these diseases. Those with mutations in polycystic kidney disease genes formed balloon like, fluid filled sacks, called cysts, from kidney tubules. The organoids with mutations in podocalyxin, a gene linked to glomerulonephritis, lost connections between filtering cells.

"Mutation of a single gene results in changes kidney structures associated with human disease, thereby allowing better understand of the disease and serving as models to develop therapeutic agents to treat these diseases," explained Joseph Bonventre, senior author of the study. He is chief of the Renal Division at Brigham and Women's Hospital and a principal faculty member at Harvard Stem Cell Institute.

"These genetically engineered mini-kidneys," Freedman added, "have taught us that human disease boils down to simple components that can be re-created in a petri dish. This provides us with faster, better ways to perform 'clinical trials in a dish' to test drugs and therapies that might work in humans."

The researchers found that genetically matched kidney organoids without disease-linked mutations showed no signs of either disease.

"CRISPR can be used to correct gene mutations," explained Freedman. "Our findings suggest that gene correction using CRISPR may be a promising therapeutic strategy."

In the United States, costs for kidney disease are about 40 billion dollars per year. Kidney disease affects approximately 700 million people worldwide. Twelve million patients have polycystic kidney disease and two million gave complete kidney failure. Dialysis and kidney transplantation, the only options for patients in kidney failure, can cause harmful side effects and poor quality-of-life.

"As a result of this new technology," Freedman said, "we can now grow, on demand, new kidney tissue that is 100 percent immunocompatible with an individual's own body."

He added, "We have shown that these tissues can mimic both healthy and diseased kidneys, and that the organoids can survive in mice after being transplanted. The next question is whether the organoids can perform the functions of kidneys after transplantation."

source: University of Washington Health Sciences/UW Medicine