Scientists at the U.S. Department of Energy's Argonne National Laboratory attacked a tangled problem by developing a new technique to grow tiny "hairy" materials that assemble themselves at the microscale.

The key ingredient is epoxy, which is added to a mixture of hardener and solvent inside an electric cell. Then the scientists run an alternating current through the cell and watch long, twisting fibers spring up. It looks like the way Chia Pets grow in commercials.

"The process is very simple, the materials are cheap and available and they can grow on almost every surface we've tried," said Argonne physicist Igor Aronson, who co-authored the study.

By tweaking the process, the team can grow many different shapes: short forests of dense straight hairs, long branching strands or "mushrooms" with tiny pearls at the tips. Interestingly, though the structures can be permanent, the process is also instantly reversible.

"This is a completely new kind of structure," said Argonne physicist Alexey Snezhko, also a co-author. "With this method, you can support more complex structures that have unique properties."

Scientists are very interested in materials with tiny fibers for technologies like batteries, photovoltaic cells or sensors. For one, "hairy" materials offer up a lot of surface area. Many chemical reactions depend on two surfaces making contact with one another, so a structure that exposes a lot of surface area will speed the process along. (For example, grinding coffee beans gives the coffee more flavor than soaking whole beans in water.) Micro-size hairs can also make a surface that repels water, called superhydrophobic, or dust.

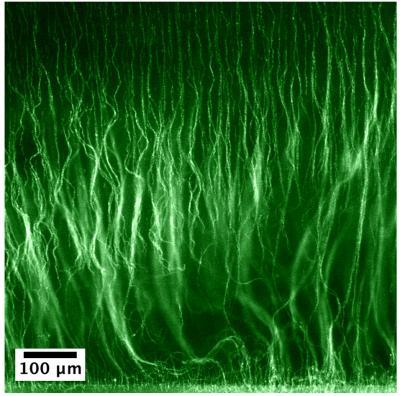

Argonne materials scientists announced a new technique to grow these little forests at the microscale (the scale shows 100 micrometers, which is about the diameter of a single human hair).

(Photo Credit: Image by Alexey Snezhko and Igor Aronson, Argonne National Laboratory)

The tiny-fiber structure is so useful that it's evolved several times in nature, Aronson pointed out. For example, blood vessels are lined with a layer of similar tiny protein "hairs," thought to help reduce wear and tear by blood cells and bacterial infections, among other properties.

Currently, the primary methods of creating interesting shapes at small scales is lithography, a type of "printing" where researchers lay a pattern on the material and the rest of it is melted or etched away. But it's hard to make very complex structures with this method; it's hard to control; and the results aren't always uniform.

"These polymers assemble themselves," Snezhko explained, "which is much easier and less labor-intensive than lithography."

In one experiment the researchers used a process called atomic layer deposition that deposits a molecule-thick layer of material over the entire hairy structure, like a fresh blanket of snow, to add a layer of semiconductor material. Semiconductors are essential ingredients in many technologies, such as solar cells and electronics.

This provided proof of concept that the polymer could be incorporated into semiconductor-based renewable energy technologies. It also proved that it could survive high temperatures, up to 150°C, an essential property for many manufacturing processes.

Right now the structures are about a single micron thick—you could stack 100 of them to reach the width of a sheet of paper. Aronson and Snezhko said their next goal is to get them even smaller, to the nanoscale.

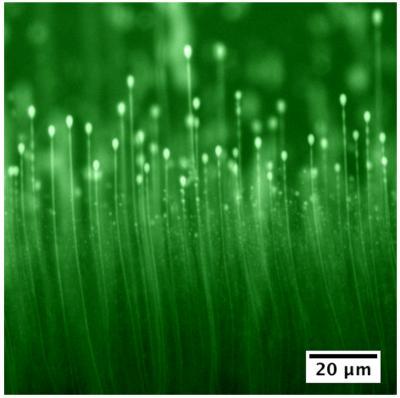

These tiny "mushrooms" could be useful in new energy technologies. By tweaking the process, scientists can grow a variety of shapes and sizes. The scale bar shows 20 micrometers, which is about the size of a single bacterium.

(Photo Credit: Image by Alexey Snezhko and Igor Aronson, Argonne National Laboratory)

These tiny "hairs" assemble themselves almost instantly when scientists apply an alternating electrical current. The entire field of view is smaller than the thickness of a credit card. Argonne National Laboratory scientists Alexey Snezhko and Igor Aronson developed this technique, which can grow all kinds of shapes with different tweaks. The "hairy" materials could be useful in next-generation energy technologies, like new and better kinds of batteries.

Read more at http://www.anl.gov/articles/good-hair-day-new-technique-grows-tiny-hairy-materials-microscale-0.

(Photo Credit: Video courtesy Alexey Snezhko and Igor Aronson, Argonne National Laboratory)

Source: DOE/Argonne National Laboratory