Unique finds of original pigment in fossilised skin from three multi-million-year old marine reptiles attract considerable attention from the scientific community. The pigment reveals that these animals were, at least partially, dark-coloured in life, which is likely to have contributed to more efficient thermoregulation, as well as providing means for camouflage and UV protection. Researchers at Lund University are among the scientists that made the spectacular discovery.

During the Age of the dinosaurs, huge reptiles, such as mosasaurs and ichthyosaurs, ruled the seas. Previously, scientists could only guess what colours these spectacular animals had; however, pigment preserved in fossilised skin has now been analysed at SP Technical Research Institute of Sweden and MAX IV Laboratory, Lund University, Sweden. The unique soft tissue remains were obtained from a 55 million-year-old leatherback turtle, an 85 million-year-old mosasaur and a 196 million-year-old ichthyosaur. This is the first time that the colour scheme of any extinct marine animal has been revealed.

"This is fantastic! When I started studying at Lund University in 1993, the film Jurassic Park had just been released, and that was one of the main reasons why I got interested in biology and palaeontology. Then, 20 years ago, it was unthinkable that we would ever find biological remains from animals that have been extinct for many millions of years, but now we are there and I am proud to be a part of it", said Johan Lindgren about the discovery of the ancient pigment molecules.

Preserved pigment in fossilized skin from a leatherback turtle, a mosasaur and an ichthyosaur suggests that these animals were, at least partially, dark-colored in life -- an example of convergent evolution. Note that the leatherback turtle and mosasaur have a dark back and light belly (a color scheme also known as countershading), whereas the ichthyosaur, similar to the modern deep-diving sperm whale, is uniformly dark-colored.

(Photo Credit: Illustration by Stefan Sølberg)

Johan Lindgren is a scientist at Lund University in Sweden, and he is the leader of the international research team that has studied the fossils. Together with colleagues from Denmark, England and the USA, he now presents the results of their study in the scientific journal Nature. The most sensational aspect of the investigation is that it can now be established that these ancient marine reptiles were, at least partially, dark-coloured in life, something that probably contributed to more efficient thermoregulation, as well as providing means for camouflage and protection against harmful UV radiation.

The analysed fossils are composed of skeletal remains, in addition to dark skin patches containing masses of micrometre-sized, oblate bodies. These microbodies were previously interpreted to be the fossilised remains of those bacteria that once contributed to the decomposition and degradation of the carcasses. However, by studying the chemical content of the soft tissues, Lindgren and his colleagues are now able to show that they are in fact remnants of the animals' own colours, and that the micrometre-sized bodies are fossilised melanosomes, or pigment-containing cellular organelles.

"Our results really are amazing. The pigment melanin is almost unbelievably stable. Our discovery enables us to make a journey through time and to revisit these ancient reptiles using their own biomolecules. Now, we can finally use sophisticated molecular and imaging techniques to learn what these animals looked like and how they lived", said Per Uvdal, one of the co-authors of the study, and who works at the MAX IV Laboratory.

This is a photo of spectacular soft tissue fossils. To the left, there is skin from a 55 million-year-old leatherback turtle (scale bar, 10 cm). In the centre, there are scales from an 85 million-year-old mosasaur (scale bar, 10 mm). To the right, there is a tail fin from a 196 million-year-old ichthyosaur (scale bar, 5 cm).

(Photo Credit: Photographs by Bo Pagh Schultz, Johan Lindgren and Johan A. Gren, respectively)

Mosasaurs (98 million years ago) are giant marine lizards that could reach 15 metres in body length, whereas ichthyosaurs (250 million years ago) could become even larger. Both ichthyosaurs and mosasaurs died out during the Cretaceous Period, but leatherback turtles are still around today. A conspicuous feature of the living leatherback turtle, Dermochelys, is that it has an almost entirely black back, which probably contributes to its worldwide distribution. The ability of leatherback turtles to survive in cold climates has mainly been attributed to their huge size, but it has also been shown that these animals bask at the sea surface during daylight hours. The black colour enables them to heat up faster and to reach higher body temperatures than had they instead been lightly coloured.

"The fossil leatherback turtle probably had a similar colour scheme and lifestyle as does Dermochelys. Similarly, mosasaurs and ichthyosaurs, which also had worldwide distributions, may have used their darkly coloured skin to heat up quickly between dives", said Johan Lindgren.

If their interpretations are correct, then at least some ichthyosaurs were uniformly dark-coloured in life, unlike most living marine animals. However, the modern deep-diving sperm whale has a similar colour scheme, perhaps as camouflage in a world without light, or as UV protection, given that these animals spend extended periods of time at or near the sea surface in between dives. The ichthyosaurs are also believed to have been deep-divers, and if their colours were similar to those of the living sperm whale, then this would also suggest a similar lifestyle, according to Lindgren.

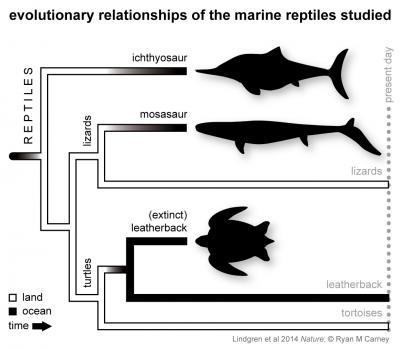

This photo shows the evolutionary relationships of the three fossil marine reptiles examined in the study. Note that each lineage independently became secondarily aquatically adapted. Black branches indicate life in the sea, whereas white branches symbolize life on land.

(Photo Credit: Illustration by Ryan M. Carney)

Source: Lund University