Vultures are poor flappers and need to soar in order to fly, relying on updrafts to gain altitude. Spend enough time watching vultures, though, and you'll notice them wobbling at low altitudes as well as circling high in the air. New research in The Auk: Ornithological Advances shows how vultures use small-scale turbulence to stay aloft even when weather conditions don't favor the formation of thermals. The mechanism and purpose of this behavior, which researchers have dubbed 'contorted soaring,' are explained for the first time in the forthcoming article.

Julie Mallon of West Virginia University (now at the University of Maryland) and her colleagues observed vulture behavior at thirteen sites in southeastern Virginia in 2013 and 2014. They found that both Turkey Vultures (Cathartes aura) and Black Vultures (Coragyps atratus) used contorted soaring primarily when the weather was cool and cloudy, conditions not optimal for the development of thermals, and when flying less than fifty meters above the ground. The researchers believe that the vultures were making use of small-scale turbulence that forms when horizontal air currents hit the edge of a forest or a similar barrier, producing a small area of uplift at the tree line.

Using this sort of small-scale turbulence in addition to other sources of updrafts appears to increase the amount of time vultures can spend on the wing, searching for food. Turkey Vultures may especially benefit from low-altitude contorted soaring -- they use their sense of smell to find carrion in forests, and by flying along the edge of the trees they have a better chance of finding food while avoiding the notice of higher-flying Black Vultures that might otherwise compete with them for carcasses.

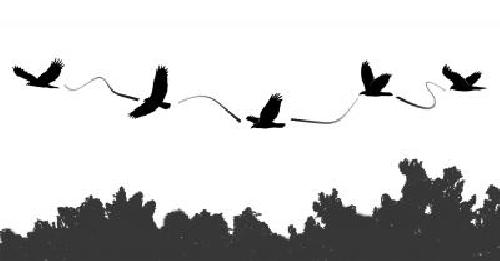

Vultures use small-scale turbulence to stay aloft at forest edges, a behavior that researchers have dubbed "contorted soaring." Credit: M. DiGiorgio

Vultures use small-scale turbulence to stay aloft at forest edges, a behavior that researchers have dubbed "contorted soaring." Credit: M. DiGiorgio

Although ecological research increasingly uses high-tech approaches to data collection, this project used an 'old-school' observational approach, watching vultures through binoculars and recording how long they spend at different altitudes and using different types of flight. "Finding vultures to observe was the easiest part of our field work: My field technician and I would sit in camping chairs by the side of the road and wait for the vultures to come to us," says Mallon. "Out of curiosity, locals would often stop and ask us why we were there. After a few weeks, we became quite famous and people would stop just to tell us that they had heard about us!

"We now know soaring flight is more complex than previously thought and merits more study," she adds. "Although observational studies are less and less common in the ornithological literature, it is very satisfying that we were able to add this basic knowledge with such a simple approach."

source: Central Ornithology Publication Office