By the time they realized that the lens was not one star, but two, they had captured a considerable amount of data—and made a surprising discovery: the distortion.

Weeks after all signs of the planet had faded, the light from the binary-lens caustic crossing became distorted, as if there were a kind of echo of the original planet signal.

Intensive computer analysis by professor Cheongho Han at Chungbuk National University in Korea revealed that the distortion contained information about the planet—its mass, separation from its star, and orientation—and that information matched perfectly with what astronomers saw during their direct observation of the dip due to the planet. So the same information can be captured from the distortion alone.

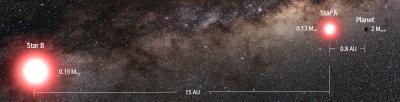

This detailed analysis showed that the planet is twice the mass of Earth, and orbits its star from an Earth-like distance, around 90 million miles. But its star is 400 times dimmer than our sun, so the planet is very cold—around 60 Kelvin (-352 degrees Fahrenheit or -213 Celsius), which makes it a little colder than Jupiter's moon Europa. The second star in the star system is only as far from the first star as Saturn is from our sun. But this binary companion, too, is very dim.

Still, binary star systems composed of dim stars like these are the most common type of star system in our galaxy, the astronomers said. So this discovery suggests that there may be many more terrestrial planets out there—some possibly warmer, and possibly harboring life.

Three other planets have been discovered in binary systems that have similar separations, but using a different technique. This is the first one close to Earth-like size that follows an Earth-like orbit, and its discovery within a binary system by gravitational microlensing was by chance.

"Normally, once we see that we have a binary, we stop observing. The only reason we took such intensive observations of this binary is that we already knew there was a planet," Gould said. "In the future we'll change our strategy."

In particular, Gould singled out the work of amateur astronomer and frequent collaborator Ian Porritt of Palmerston North, New Zealand, who watched for gaps in the clouds on the night of April 24 to get the first few critical measurements of the jump in the light signal that revealed that the planet was in a binary system. Six other amateurs from New Zealand and Australia contributed as well.

This artist's rendering depicts a newly discovered frozen planet orbiting one star of a binary star system 3,000 light-years from Earth, and shows what the two dim stars in the binary system might look like from the view of the planet. The discovery, made by a collaboration of international research teams and led by researchers at The Ohio State University, expands astronomers' notions of where to look for planets in our galaxy.

(Photo Credit: Movie by Cheongho Han, Chungbuk National University, Republic of Korea.)

This artist's rendering shows a newly discovered planet (far right) orbiting one star (right) of a binary star system. The discovery, made by a collaboration of international research teams and led by researchers at The Ohio State University, expands astronomers' notions of where to look for planets in our galaxy.

(Photo Credit: Image by Cheongho Han, Chungbuk National University, Republic of Korea.)

Source: Ohio State University