Treating influenza relies on drugs such as Amantadine that are becoming less and less effective due to viral evolution. But University of Chicago scientists have published computational results that may give drug designers the insight they need to develop the next generation of effective influenza treatment.

"It's very hard to design a drug if you don't understand how the disease functions," said Gregory Voth, the Haig P. Papazian Distinguished Service Professor in Chemistry. Voth and three co-authors offer new insights into the disease's functioning in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences Online Early Edition for the week of June 16-20, 2014.

Amantadine is a bulky organic compound originally designed to treat influenza A by blocking proton flow through the M2 channel, one of the few proteins that are targets for antiviral therapies. "The proton flow is essential for influenza viral replication," said Voth, who also is director of the Center for Multiscale Theory and Simulation. Unfortunately, subsequent mutations in different forms of the flu have changed the ability of Amantadine to bind to the M2 protein. "There's a big, worldwide push to find new drugs that will block this or other influenza proteins," Voth said.

Route to new, better drugs

"Dr. Voth and his colleagues have simulated the process of proton transfer through the M2 channel and the effects of mutations that cause resistance to drugs that block this channel at a level of detail not previously possible," said Dr. Peter Preusch of the National Institutes of Health's National Institute of General Medical Sciences, which funded the research. "This work helps expand the methods for molecular simulation available to researchers and may eventually lead to new and better drugs to treat influenza infections."

The UChicago team conducted extensive multiscale simulations of proton permeation, a critical step in viral replication, through the M2 channel from influenza A. The simulations enabled them to visualize this process at three interconnected scales, from the electronic (the smallest), to the molecular (intermediate) to the mesoscopic (the largest). The capability of the technique was demonstrated by last year's Nobel Prize in Chemistry, which was awarded to three scientists "for the development of multiscale models for complex chemical systems."

"Computer simulation, when done very well, with all the right physics, reveals a huge amount of information that you can't get otherwise," Voth said. "In principle you could do these calculations with potential drug targets and see how they bind and if they are in fact effective."

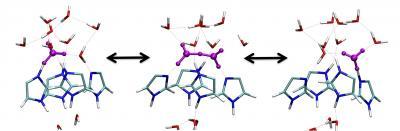

Multiscale computer simulations show the molecular details of the flow of protons shuttling between specific water molecules (purple) through the influenza A protein for the first time. The red and white figures represent additional water molecules, while the blue-green figures show the histidine amino acid residues that assist this proton flow at the "heart" of the M2 channel within the protein. Scientists and drug designers have sought to understand the M2 channel at this level of detail for two decades.

(Photo Credit: Ruibin Liang/University of Chicago)

The flow of protons through the watery M2 channel is a complex process, one involving many phenomena, including the making and breaking of chemical bonds. Scientists have attempted to simulate this process computationally for more than 20 years to understand how it works, but only now has the feat been achieved. No other experimental or simulation technique is capable of examining the proton flow process in such detail.

Scientists have, however, succeeded in experimentally producing mutations of different parts of the M2 protein. The UChicago team's simulations of the protein's dynamics not only agree with those experimental data, which validates the results, but also explains the effects of these mutations, one of which is a dominant cause of drug resistance.

Yearlong high-performance operation

To reach such significant conclusions, the UChicago team tapped the power of four high-performance computer clusters. Principal among these was the Midway high performance computing cluster at the University's Research Computing Center. The Midway cluster worked various aspects of the problem continually for an entire year under the watchful guidance of Ruibin Liang, a graduate student in chemistry and the study's lead author.

But the team also needed clusters at the Texas Advanced Computing Center at the University of Texas at Austin, the San Diego Supercomputer Center at the University of San Diego, and the Department of Defense High Performance Computing Center in Vicksburg, Miss.

The University of Chicago's Gregory Voth is the Haig P. Papazian Distinguished Service Professor in Chemistry and director of the Center for Multiscale Theory and Simulation.

(Photo Credit: Jason Smith)

"This was a huge amount of work, so I used every resource available. Professor Voth devoted a lot of machine time to this project," Liang said.

More work lies ahead for Voth and his team, including trying to make the simulation process run more quickly, explaining the effects of drug resistant mutations, and targeting other forms of influenza. According the Liang, the stage has been set and the work is underway to reveal the proton permeation mechanism in influenza B, another form of the flu that has a different M2 channel and is entirely resistant to drugs like Amantidine.

The University of Chicago's Ruibin Liang is a graduate student in chemistry and lead author of a new paper on influenza A virus replication published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

(Photo Credit: Andrew Nelles)

Source: University of Chicago