In a new evolutionary proof of the old adage, 'we are what we eat', Cornell University scientists have found tantalizing evidence that a vegetarian diet has led to a mutation that -- if they stray from a balanced omega-6 to omega-3 diet -- may make people more susceptible to inflammation, and by association, increased risk of heart disease and colon cancer.

The discovery, led by Drs. Tom Brenna, Kumar Kothapalli, and Alon Keinan provides the first evolutionary detective work that traces a higher frequency of a particular mutation to a primarily vegetarian population from Pune, India (about 70 percent), when compared to a traditional meat-eating American population, made up of mostly Kansans (less than 20 percent). It appears in the early online edition of the journal Molecular Biology and Evolution.

By using reference data from the 1000 Genomes Project, the research team provided evolutionary evidence that the vegetarian diet, over many generations, may have driven the higher frequency of a mutation in the Indian population. The mutation, called rs66698963 and found in the FADS2 gene, is an insertion or deletion of a sequence of DNA that regulates the expression of two genes, FADS1 and FADS2. These genes are key to making long chain polyunsaturated fats. Among these, arachidonic acid is a key target of the pharmaceutical industry because it is a central culprit for those at risk for heart disease, colon cancer, and many other inflammation-related conditions. Treating individuals according to whether they carry 0, 1, or 2 copies of the insertion, and their influence on fatty acid metabolites, can be an important consideration for precision medicine and nutrition.

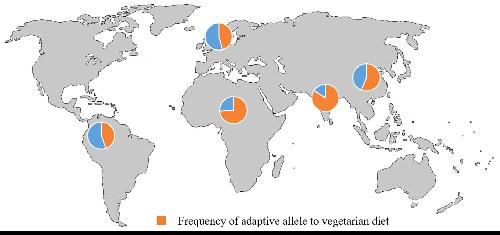

Worldwide map shows frequency of an adaptive allele to a vegetarian diet.

Worldwide map shows frequency of an adaptive allele to a vegetarian diet.

By using reference data from the 1000 Genomes Project, a Cornell research team provided evolutionary evidence that the vegetarian diet, over many generations, may have driven the higher frequency of a mutation in the Indian population.

The mutation, called rs66698963 and found in the FADS2 gene, is an insertion or deletion of a sequence of DNA that regulates the expression of two genes, FADS1 and FADS2. These genes are key to making long chain polyunsaturated fats. Among these, arachidonic acid is a key target of the pharmaceutical industry because it is a central culprit for those at risk for heart disease, colon cancer, and many other inflammation-related conditions.

Treating individuals according to whether they carry 0, 1, or 2 copies of the insertion, and their influence on fatty acid metabolites, can be an important consideration for precision medicine and nutrition. Credit: J. Thomas Brenna, Cornell University

The insertion mutation may be favored in populations subsisting primarily on vegetarian diets and possibly populations having limited access to diets rich in polyunsaturated fats, especially fatty fish. Very interestingly, the deletion of the same sequence might have been adaptive in populations which are based on marine diet, such as the Greenlandic Inuit. The authors will follow up the study with additional worldwide populations to better understand the mutations and these genes as a genetic marker for disease risk.

"With little animal food in the diet, the long chain polyunsaturated fatty acids must be made metabolically from plant PUFA precursors. The physiological demand for arachidonic acid, as well as omega-3 EPA and DHA, in vegetarians is likely to have favored genetics that support efficient synthesis of these key metabolites." say Brenna and Kothapalli in a joint comment. "Changes in the dietary omega-6 to omega-3 balance may contribute to the increase in chronic disease seen in some developing countries."

"This is the most unique scenario of local adaptation that I had the pleasure of helping uncover", says Alon Keinan, a population geneticist who led the evolutionary study. "Several previous studies pointed to recent adaptation in this region of the genome. Our analysis points to both previous studies and our results being driven by the same insertion of an additional small piece of DNA, an insertion which has a known function. We showed this insertion to be adaptive, hence of high frequency, in Indian and some African populations, which are vegetarian. However, when it reached the Greenlandic Inuit, with their marine diet, it became maladaptive." Kaixiong Ye, a postdoctoral research fellow at Keinan's lab, further notes that "our results show a global frequency pattern of the insertion mutation adaptive to vegetarian diet (see figure), with highest frequency in Indians who traditionally relied heavily on a plant-based diet."

source: Molecular Biology and Evolution (Oxford University Press)