WASHINGTON, June 19, 2014—Before they excise a tumor, surgeons need to determine exactly where the cancerous cells lie. Now, research published today in The Optical Society's (OSA) journal Optics Letters details a new technique that could give surgeons cheaper and more lightweight tools, such as goggles or hand-held devices, to identify tumors in real time in the operating room.

The new technology, developed by a team at the University of Arizona and Washington University in St. Louis, is a dual-mode imager that combines two systems—near-infrared fluorescent imaging to detect marked cancer cells and visible light reflectance imaging to see the contours of the tissue itself—into one small, lightweight package approximately the size of a quarter in diameter, just 25 millimeters across.

"Dual modality is the path forward because it has significant advantages over single modality," says author Rongguang Liang, associate professor of optical sciences at the University of Arizona.

Interest in multi-modal imaging technology has surged over the last 10 years, says Optics Letters topical editor Brian Applegate of Texas A&M University, who was not involved in the research. People have realized that in order to better diagnose diseases like cancer, he says, you need information from a variety of sources, whether it's fluorescence imaging, optical imaging or biochemical markers.

"By combining different modalities together, you get a much better picture of the tissue," which could help surgeons make sure they remove every last bit of the tumor and as small amount of healthy tissue as possible, Applegate says.

Currently, doctors can inject fluorescent dyes into a patient to help them pinpoint cancer cells. The dyes converge onto the diseased cells, and when doctors shine a light of a particular wavelength onto the cancerous area, the dye glows. In the case of a common dye called indocyanine green (ICG), it glows in near-infrared light. But because the human eye isn't sensitive to near-infrared light, surgeons have to use a special camera to see the glow and identify the tumor's precise location.

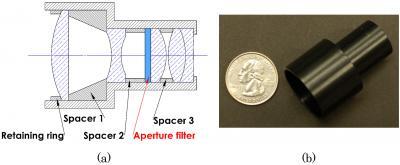

This is (a) Optical and mechanical structure of the customized lens with aperture filter and (b) the photograph of the assembled lens, with a quarter for comparison.

(Photo Credit: Optics Letters)

Surgeons also need to be able to see the surface of the tissue and the tumor underneath before cutting away, which requires visible light imaging. So researchers have been developing systems that can see in both fluorescent and visible light modes.

The trouble is that the two modes have opposing needs, which makes integration difficult. Because the fluorescent glow tends to be dim, a near-infrared light camera needs to have a wide aperture to collect as much fluorescent light as possible. But a camera with a large aperture has a low depth of field, which is the opposite of what's needed for visible-light imaging.

"The other solution is to put two different imaging systems together side by side," Liang says. "But that makes the device bulky, heavy and not easy to use."

To solve this problem, Liang's group and that of his colleagues, Samuel Achilefua and Viktor Gruev at Washington University in St. Louis, created the first-of-its-kind dual-mode imaging system that doesn't make any sacrifices.

The new system relies on a simple aperture filter that consists of a disk-shaped region in the middle and a ring-shaped area on the outside. The middle area lets in visible and near-infrared light but the outer ring only permits near-infrared light. When you place the filter in the imaging system, the aperture is wide enough to let in plenty of near-infrared light. But since visible light can't penetrate the outer ring, the visible-sensitive part of the filter has a small enough aperture that the depth of field is large.

Liang's team is now adapting its filter design for use in lightweight goggle-like devices that a surgeon can wear while operating. They are also developing a similar hand-held instrument.

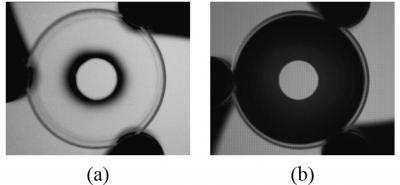

These are near-infrared (left) and visible (right) images of the aperture filter, used in the new dual-mode imager. Only the central region of the filter can transmit visible light, while the outer portion can only transmit the near-infrared light used for fluorescent imaging.

(Photo Credit: Optics Letters)

Source: The Optical Society